In 1968, when I was 13, I read Coming of Age in Samoa, by Margaret Mead. Her landmark 1928 study of adolescence had just been reissued as a 95-cent paperback for the counterculture generation. The book offered a vision of how to be a teenage girl. I could be the seductive young woman on the cover in a red sarong with a blossom in her hair—free, fearless, and lighthearted, especially about sex. It also offered a vision of how to be an intellectual woman. Mead, with her signature cape and walking stick, after all, was the most famous anthropologist in the world. And, sure enough, in that glorious period after the pill, I grew up to be free and fearless and sexually adventurous. I also grew up, naturally and effortlessly, to become a scientist and a writer. The visions came true—the possibilities were real.

This article appears in the August 2019 issue.

Check out the full table of contents and find your next story to read.

But is that actually what happened? In light of the #MeToo movement, I ask myself whether I have simply edited the threats and slights and misogyny of hippie culture out of my memories. Did I really escape the sexism of academia? I can easily call up moments that contradict my version of my past, even if at the time I dismissed them (that radical-leftist mentor, for instance, who explained to me that women could never belong to the philosophy-department faculty, because they were too distracting). And if I’m not sure that I understand my own experience and culture, how could Mead understand the unfamiliar experience and culture of the girls she observed in Samoa? The project of anthropology has always been to study people who seem very different from the anthropologists themselves. Is that project even possible? And is it worth doing?

In Gods of the Upper Air: How a Circle of Renegade Anthropologists Reinvented Race, Sex, and Gender in the Twentieth Century, Charles King, a professor of international affairs and government at Georgetown, makes the case for anthropology in a thoughtful, deeply intelligent, and immensely readable and entertaining way. The book is a joint biography of the people who created anthropology at the turn of the last century: Franz Boas, the father of the field, and the women who were among his most influential students, especially Ruth Benedict, Zora Neale Hurston, and Margaret Mead.

Boas was a German Jew born in Westphalia in 1858, and he was a generation older than his students (and had fearsome dueling scars from his days at the University of Heidelberg). He was a pathbreaking explorer—at 25, he sailed to Baffin Island, where he recorded the lives of the Inuit—and an exceptional teacher. He was also rather touchy and grumpy, with an obsessive dedication to collecting facts. Benedict, 29 years younger than Boas, was the deepest thinker of the group; her book Patterns of Culture (1934) is still an important text in anthropology. She is also an elusive figure, perhaps because the life of a lesbian university professor in the early 20th century required a certain amount of evasion. Hurston’s story is remarkable and heartbreaking. Being an intellectual woman in the 1920s was difficult enough. Being an intellectual black woman was much harder. Hurston died in 1960 at 69, neglected and penniless, and her work was rediscovered only decades later.

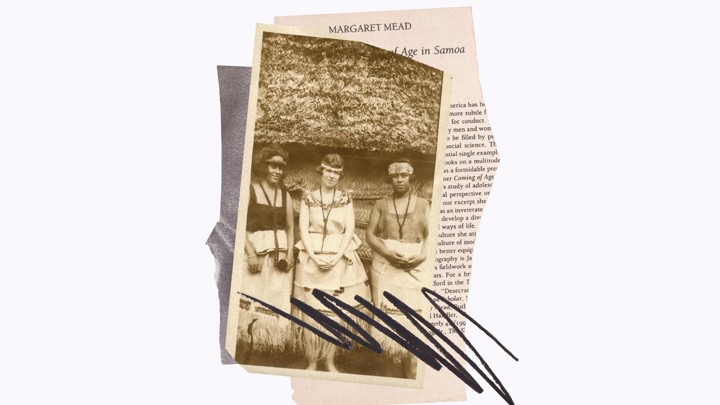

In King’s book, Margaret Mead is the magnetic center of attention, as she was in life, although she never had a tenured faculty position, and she was small and fragile—the stylish walking stick was a necessity. She was only 23 when she went to Samoa, not much more than a teenager herself. Though she had already been married for two years, she spent the long train journey to the West Coast, where the boat voyage began, talking about ideas and making passionate love to Ruth Benedict, her teacher, who was also married. Then Mead spent the long ship journey back talking about ideas and making passionate love to Reo Fortune, who became her second husband. (Airplane travel has clearly been terrible for romance.) On the next trip she met Gregory Bateson, who became her third husband after several steamy months, literally and figuratively, of sharing a hut with her and Fortune in Papua New Guinea. All this time, she wrote long, analytic letters to Benedict, trying to understand it all. For Mead, sex and ideas were inextricable.

The romantic intrigue makes for irresistible reading, but it’s also central to the book’s argument. The anthropologists had a revolutionary new idea, which they called “cultural relativity.” The phrase is a bit misleading, because it implies there is no truth to be found, but Boas and his students didn’t think that. Instead, they argued that all societies face the same basic problems—love and death, work and children, hierarchy and community—but that different societies could find different, and equally valuable, ways of solving them. Anthropologists set out to discover those ways.

The dilemmas of sex and gender and the tensions between autonomy and jealousy, adventure and commitment, identity and attraction, were especially vivid to young women of the 1920s like Mead, Benedict, and Hurston. If the 1960s felt like a cultural watershed, the period pales in comparison with the decade when these women were coming of age. Virginia Woolf said that around December 1910, human character changed, and you can feel the reverberations of that change in these stories.

Looking at how other cultures resolved those dilemmas was a way of expanding the possibilities of their own culture. The culture of Samoa was actually more complicated and contradictory than it seems in Mead’s book. But her core idea was right: In other places, there were better paths through adolescence than the tormented, repressive American one.

As you read about Mead and her lovers, you can’t help remarking on a recurrent tragicomic hopelessness about brilliant young women’s efforts to figure out sex. That’s true whether the protagonist is Mary Shelley in the 1820s, Margaret Mead in the 1920s, or a polyamorist today. You also can’t help remarking that the person at the apex of a love triangle—the position Mead found herself in again and again—is rather likely to conclude that polyamory is natural and jealousy is cultural, while the folks at the other two vertices are more likely to argue the opposite view.

More broadly, the history of feminism has seen a pendulum swing between libertine and puritan impulses. A hundred years earlier, another great feminist anthropologist working closer to home carefully studied how adolescent village girls came of age. But Jane Austen concluded that resisting male pressure and seduction was the route to empowerment, a view that may resonate more nowadays than Mead’s free love under the palm trees.

Still, the back-and-forth doesn’t mean that nothing changes, or that the project of cultural expansion is doomed. (I doubt that my granddaughter will figure out sex entirely either, but she’ll be a lot further along than Shelley or Austen—or Mead.) Neither Mead nor Benedict could fully envision the best example of 20th-century cultural transformation. They pointed out that homosexuality was accepted in other cultures and came under fire for saying it, even from other anthropologists. Edward Sapir was another famous Boas student (and another ex-lover of Mead’s), and he argued that gay sex was not just unnatural but pathological.

Benedict was the most stable and satisfying love of Margaret Mead’s early life, and another anthropologist, Rhoda Métraux, was Mead’s partner for more than 20 years. And yet the fearless, transgressive public intellectual never openly identified herself as bisexual or lesbian. Even in the 1960s, when I was reading Coming of Age, romantic love with a woman was still far outside my personal realm of possibilities—35 years passed before I discovered it.

In 2019, it’s easy to imagine Benedict and Mead settling into a happy academic marriage with a big house and kids and dogs. In 1919, it was impossible. But the anthropologists who showed how sexual patterns and expectations could vary and change helped make that kind of marriage a reality.

The very word culture, and the idea that people in one culture can learn from people in others, is taken for granted now. But King shows how revolutionary those concepts were at a time when scientists classified people as savage, barbarian, or civilized, and three-quarters of American universities offered courses in eugenics. In the 1920s, as King vividly conveys, ideas about biologically based racial, ethnic, and gender superiority were considered scientific, modern, and progressive. (In some quarters they still are.) When the Nazis looked for examples of a science that justified racial discrimination, and a government that wrote racial categories into law, they turned to the United States.

Read: What America taught the Nazis

Boas heroically led the charge against the pseudoscience of race, and his students followed, combining their academic work with public action. Hurston made her mark by her very existence as an African American woman graduate student at Columbia. Boas, Benedict, and Mead also dedicated themselves to fighting the forces of populist xenophobia before and during World War II. Even more striking, after the war, Benedict’s famous book The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture (1946) was an explicit attempt to combat anti-Japanese bias.

At the end of the 20th century, anthropology went through an intellectual and moral crisis. The malign influence of postmodernism, which actually did advocate a profound relativism, played a part. Yet the crisis was also an appropriate reaction to a real problem—privileged members of one culture were parachuting in to study the threatened and oppressed members of other cultures. The result was a kind of paralysis. If people from one culture couldn’t say anything about people from another, for both political and philosophical reasons, why do anthropology at all?

Another development, from the opposite direction, also made anthropology problematic. The late 20th century saw the rise of sociobiology and evolutionary psychology, which largely rejected the very idea that cultural difference and change were important. Mead’s work was attacked, in a way that now seems transparently sexist and ideologically motivated, and the unfair charge that she fabricated her data still lingers in the public imagination. Her methods, as she herself recognized, were not as careful and rigorous as later anthropologists’—she and the other pioneers were more or less making them up as they went along—but there is no doubt that her observations of Samoa were genuine and accurate.

Read: Sex, lies, and separating science from ideology

More recently, anthropology has revived itself by interacting with other disciplines. Inspired by evolutionary biology, behavioral ecologists such as Sarah Hrdy of UC Davis study how basic biological imperatives—child care, for example—play out in different societies. Inspired by cognitive science, cognitive anthropologists such as Rita Astuti of the London School of Economics study how intuitive theories of kinship and death develop in different cultures. Stanford’s T. M. Luhrmann, and other anthropologists of religion, study how different cultural models of the mind configure religious experience. (Women are still exceptionally prominent in the field—an important legacy of those early figures.) Psychologists and economists are also starting to appreciate the need to study cultures beyond what are known as the WEIRD (Western-educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic) ones.

Our very conceptions of biology and culture are changing, and the new ideas redeem the vision of the anthropological pioneers. The old distinctions between biology and culture, nature and nurture, just don’t work. Today, it’s clear that culture is our nature, and the ability to change is our most important innate trait. Human beings are uniquely, biologically gifted at imagining new ways that people and the world could be, and transmitting those new possibilities to the next generation. Human imagination and cultural transformation go hand in hand. Some of the most important current work in anthropology, biology, and psychology looks at the mechanisms that allow cultural transmission and change across generations. Children’s brains are biologically adapted both to innovate and to learn from their elders, and teenagers, in particular, are often at the cutting edge of cultural change. Mead’s focus on childhood and adolescence was prescient.

The girls of Samoa showed Mead that there was a different way to grow up, a different way to become a woman. Mead’s book passed on that sense of other possibilities to me. The early anthropologists made us realize just how many ways there are to be human.

This article appears in the August 2019 print edition with the headline “The Students of Sex and Culture.”

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.